This is a review of a television show with a TV-MA rating because of profanity. Many Christians may feel like they ought not to watch media like this. Please abide by your conscience. If you aren’t sure about what content is permissible to consume, you can read this guide I wrote up, or this one from Brett McCracken.

A woman lies unconscious on a coffin-shaped conference table. She is dressed professionally, but is sprawled out like she is recovering from a night of drinking. The windowless room has a mid-century modern feel to it; green and yellow carpet, chic chairs, dark wood. A small speaker at her head chirps out: “Who are you?”

She stirs, blinks, gets up. “Who are you?” The woman slurs her words, puzzles at the voice, and begins to get off the table. The speaker continues to chirp as she stumbles around. She has been drugged, apparently, and has no idea where she is. She tries the door, but it is locked. The speaker apologizes, says she must first answer the questions. She screams at the speaker to let her go, prowls around the room, again tries to break the door down. But it won’t work.

She stops her pacing, Fine then. She finally gives in, is willing to answer the childish question. Only, when she goes to do it, she can’t. She has no idea who she is. “What state were you born in?” She has no idea. “What color are your mother’s eyes?” Nothing. A deeper, more unraveling panic sets in. Her mind, her memories, her sense of self all are gone.

Imagine you could shut your brain off for eight hours a day. You could bend the line of time together and just pinch off a loop, toss it aside. We, of course, do that every time we sleep. But imagine that instead of lying in bed, you could be doing something productive? Imagine you are working some dead end job and could just hit the fast-forward button so that your waking self only experienced you walking in, and then walking out.

This was what was running through Dan Erickson’s mind while working a tedious desk job. He had moved to LA with the hopes of becoming a writer, but the only job he could get was in the office of a door factory. Everyday he sat in a windowless office, cataloging different door components: hinges, knobs, etc. And everyday he would think:

I wish I could just jump to the end of the day…I wish I could just not experience the next eight hours of my life.

…

And then…the show was more or less fully conceived within the next five minutes.

Who Are You?

Severance (Apple TV+), follows the main character Mark Scout (played by Adam Scott), a shell of a person who has been hollowed out by grief over the death of his wife. Suffering has not made him stronger but reduced him to falling asleep drunk to the television every night, avoiding his family, avoiding counseling, avoiding life. So committed to this mode of being, he decides to have a microchip implanted in his brain by his employer, Lumon Industries, to create a “severed” form of himself: as the elevator dings to his floor at work, Mark’s conscious self shuts off and a new version of him wakes up, scrubbed clean of any outside memories. In the blink of an eye, Mark’s “outie” self is back in the elevator, hearing the ding as the doors open at the end of the day, wholly unaware of what he has been doing for the past eight hours.

The show’s philosophical heart revolves around the classic question introduced at the opening scene: Who are you? Only, it seeks to wrestle with it in this bizarrely dystopian (microchips in brains) yet quaint, familiar setting: the workplace.

Hey kids, what’s for dinner?

For most of human history, “work” did not look like a 9-5. There was the occasional genius or artist who was supported by a patron, but most normal people worked some kind of trade: butchers, bakers, candlestick makers. And your work was a seamless part of the rest of your life. You most likely operated your craft out of your home, your family participated in the labor, and the other affairs of the household were part of what you considered your “work.” You may start the day cutting leather or hammering horseshoes, but you also needed to tend the garden, feed the livestock, and chop firewood. Though your work would be from dusk to dawn (and probably involve manual labor), it wasn’t a “grind.” In fact, you probably worked less than we do today.1

The industrial revolution in 19th century changed all that.

Your job became this wholly other thing from the rest of your life. You went to the factory, the call-center, the plant. Eventually, people started speaking about “work-life balance” because, for the first time, “work” and “life” were separate. And one threatened to eat the other. The concept of the eight-hour workday was a hard-won victory for the average working man: Eight hours to sleep, eight hours to work, eight hours to do what one wills. Yet, like a creeping fungus, work continued to take more and more.

For many their life is their work. In pre-industrial Britain, one third of the year was set aside for holidays, feasts, and Sabbath rests.2 Today, Americans take on average ten days of vacation a year. Sitcoms set in the 80’s and before centered on the home and family (Growing Pains, Full House); in the 90’s it centered on friends (Seinfeld, Friends); and then in the 2000’s it was the work place (The Office, Parks and Rec). More and more, as people imagined what life was like, it moved away from the home and into the work place. Why? Because, more and more, that was where we spent most of our time.

Severance preys upon this feeling. The concept of the severance procedure is immediately appealing: what if you never had to work? And also terrifying: what if you never left?

When Irving, (played by John Turturro), walks into the office he light-heartedly asks: Hey kids, what’s for dinner? His co-workers groan; it’s banter, it’s silly, it somehow fits with Irving’s quirkiness. But the comment is a question a dad would normally utter as he hangs up his jacket returning from work, something you’d almost expect a television dad to say as he walks into the house in an episode of Leave It To Beaver; something someone says when they come home to their family.

The severed Irving has no home, has no family. His entire conscious experience is there in that fluorescent office. All he has is work.

Come Now, Children of My Industry

The company the show centers on, Lumon, is an enormous monolith, a mega-corporation on par with Apple or Google or Pfizer, but begun in the era of the industrial revolution: 1865. The company—as modern as can be—evokes the ethos of industrialization, only modernized for the age of the microchip.

The industrial revolution evokes many images, few of them charming. Smoke stacks belching out plumes; sad eyes looking out from coal-smeared faces; great machines grinding in dim factories. That’s a jaundiced perspective, of course. Industrialization brought cheaper goods and raised nations out of poverty. But with a price, always with a price. One, primarily, being that work took on a particularly dreary tone.

As industrialization turned into computerization, blue collar became white collar, many things changed. You didn’t go to the mines or ether factories. You went to the cubicles and offices. But there was still some element of dread and tedium that hung around, despite the motivational posters and team-building seminars.

A pre-industrial carpenter may have worked from start to finish on making a single piece of furniture. If there were one hundred different skills required to make the dresser or vanity—cutting, fitting joints, sanding, staining—he possessed them all and saw the finished product. Further, he felt a sense of pride as he looked at what he did.

But take that same piece of furniture, break the hundred steps of assembly into a hundred separate workers on an assembly line, and the sheer volume of output grows exponentially while reducing the need for artisan workers. You don’t need highly skilled workers who learn all the steps; you need a person who can master only one step. This makes work monotonous, evacuates the sense of accomplishment any worker has, and makes workers easily replaceable, like little cogs in a big machine.

The cow-eyed look of a worker on an assembly line or sitting in front of a keyboard is still cow-eyed. Both feel alienating. And especially for knowledge-workers, the joy of creating something is largely gone. Analysis, synthesis, content—all liquid, ethereal work that largely exists in the disembodied, digital netherworld. Rarely does the cubicle-warrior get to stand back and admire the finished product his craft has made.

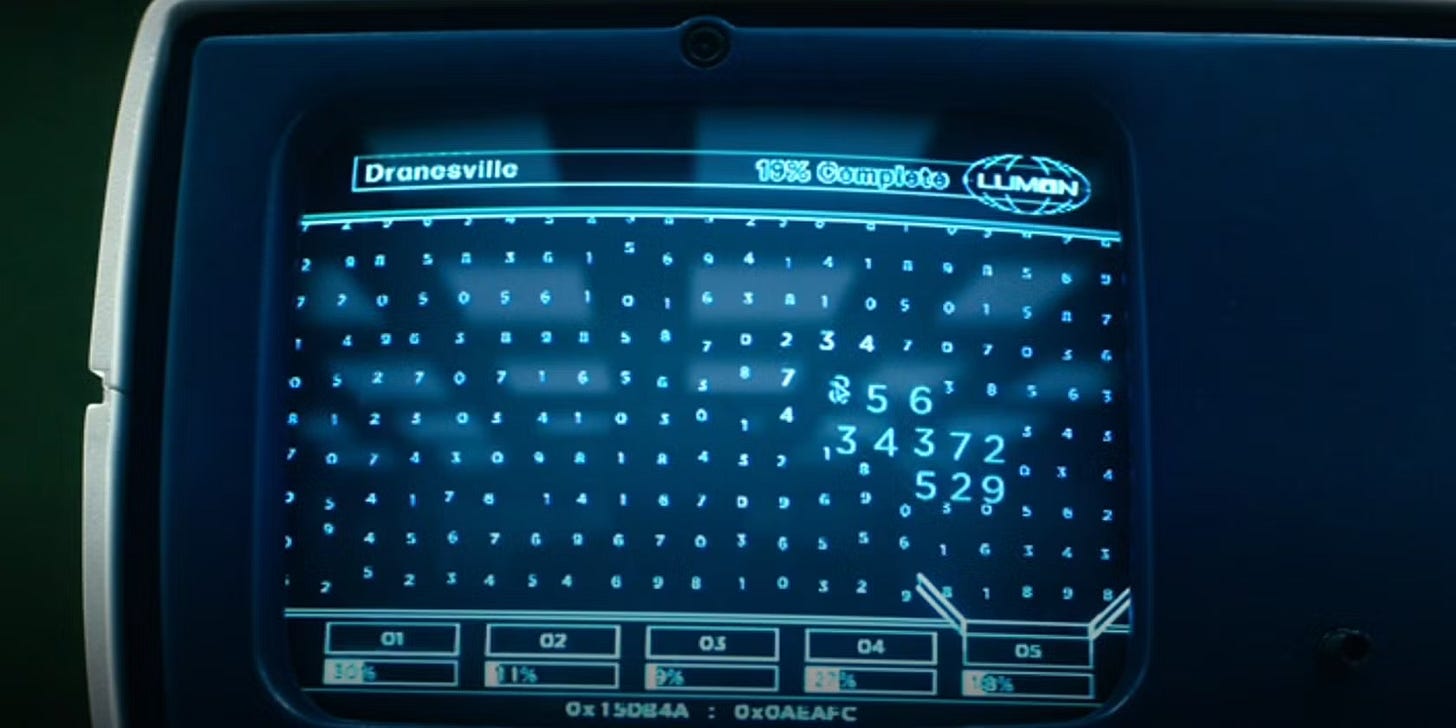

For their work, the severed employees sift through oceans of numbers on vintage CRT monitors before categorizing them—the most tedious of all tedium. All the while, they are entirely in the dark about what exactly it is they are doing. There is no sense of pride in the work they do, there is only the condescending company rewards to spur on more productivity: finger traps, caricature drawings, digital recreations of the founder telling them “I love you.” But, since the severance procedure wipes their mind of all else, these cheap Chuck-E-Cheese rewards feel very important to them. It’s all they have.

But the corporate ephemera and canned Muzak and plastic smiles on the managers’ faces strike an ominous note as you begin to learn more about this company that is prepared to drill into your skull and leave itself there.

We Serve Kier

The show resonates so deeply because it is a fantastical extension of the dread so many feel not only about work, but about life. Melancholy defines the mood of the show.3 We are weary and plagued by a malaise of meaninglessness in modern Western culture. And it isn’t just the problem of late-stage capitalism. In the past, identity, meaning, and hope often came from God, your traditions, your people. Now, if someone wants to know whether or not they are living a meaningful life, they tend to think about their job or the money it makes them. When you first meet someone, when you are trying to find out who they are, what do you ask? What do you do? What questions do we ask our children? What do you want to be when you grow up?

And yet, these careers, which we are pushed towards from an early age, frequently feel disorienting, dull, and disappointing. And our severance (wink-wink) from the traditions and religions of the past leave us ill-equipped to deal with the slings and arrows of life.

Mark’s decision to splice his brain in half is a picture of a man who has been so diminished internally that he has no resources to deal with the inevitable sorrows of life—no sacred story to tell himself, no community of faith, no prayers or rituals to move him through the stages of grief. He only has the technocratic salvation of pacifying his pain by minimizing the number of hours he is conscious. We may lack that technology today, but we have a facsimile of it with our own versions of “shutting our brains off”: scrolling, binging, distracting ourselves to death.

Severance weaves together our hunger for meaning and identity, how careers fail to deliver those, and the role of technology to numb the pain. But it turns the dial up even further by turning to the role of religion.

What if work didn’t just eat up your weekends and your emotional energy, but what if it took over everything? The housing Mark lives in is owned by Lumon; the diner he eats at is run by Lumon; the very town itself is named after Lumon (Kier). Lumon is seemingly omnipresent and omnipotent. And like a deity, it demands unalloyed allegiance and uncompromising faith.

The upper management are not severed (that we know of) and seem to serve the company out of genuine, religious devotion. The religious world of Lumon evokes North Korean-esque leader-worship and quasi-Mormonism, but if all of that were then grafted onto Silicon Valley.

The company, founded by Kier Eagan, is a dynasty, passing from one Eagan to another. And all of the leaders seem to hold a semi-divine status. Kier, who supposedly began Lumon as a medicinal manufacturer, is far more than that. Lumon—the severance procedure itself—is a kind of gospel, a way of life to submit to, complete with a holy text (Compliance Handbook), confession (Break Room), icons (the art), and afterlife (“he sits with Kier now”). Through this the chaos within us (The Four Tempers) can be controlled and virtue can be sought (The Nine Principles).

Severed employees, who are in a sense children, are immediately folded into this cult. They must adhere to the Compliance Handbook and hit their quotas by the end of the quarter—not to keep the boss off their back—but so as to not disappoint Kier.

The You You Are

The cult of Lumon is essentially a means of control, an opiate of the masses. And it is apparently unsatisfying. When a copy of a self-help book, The You You Are: A Spiritual Biography of You—an utterly ridiculous, shallow book—winds up in the hands of severed Mark, he furtively begins to read it. Like cheesy self-help, the book offers inane truisms about believing in yourself and how no one—particularly not your boss—can tell you who you are.

What separates man from machine is that machines can not think for themselves. Also they are made of metal, whereas man is made of skin.

…

A society with festering workers cannot flourish, just as a man with rotting toes cannot skip.

…

In the center of industry is dust.4

The lines in the book are so stupid that they make the audience laugh, but they are not stupid to Mark—they are life changing. It’s a brilliant bit of writing by the show’s creator, Dan Erickson. He manages to somehow skewer the pretentious, faux-progressive-intellectualism represented by the book, while also showing that in a world as bleak as the severed floor of Lumon, even vapid, fortune-cookie spirituality is life-giving. Further, it is another way that the show’s main theme continues to be centered: who are you?

The Good News About Hell

In the first episode, Mark’s boss, tells him:

My mother was an Atheist, and she used to say there’s good news and bad news about Hell. The good news is Hell is just the product of a morbid human imagination. The bad news is whatever humans can imagine they can usually create.

The severed floor of Lumon is a kind of hell that represents the sum total of our greatest fears of modern life. What happens to people who are spiritually diminished, relationally isolated, and left with no locus of meaning except their careers? Their careers, dreary though they may be, swallow them; the technology they create controls them.

Severance works because the writing, acting, and cinematography are phenomenal. But it resonates so profoundly because it touches into the deepest problems that all of us sense in the modern West. We all feel like work somehow demands everything from us, yet offers little in return. We sense that we shouldn’t be afraid of the technology we create. And all the while, we are haunted by a sense of loss, an uncertainty of who we are.

Christianity offers far better news about this kind of hell. Most significantly, the Bible immediately answers who we are on the very first page: we are made in God’s image (Gen 1:26-27). And, just as God labors in the beginning (Gen 2:1-3), we too are made to work (Gen 2:15). Yes, the Bible affirms that when sin enters the world the image is now marred and so our work is cursed by toil and futility (Gen 3:17-19), but this isn’t the end. Through the work of Jesus Christ, humanity can be restored to and remade into the image of God (Rom 8:29; Col 3:10). Now, I don’t need to turn to my work to save me—Jesus does that.

We can love and serve others through our vocation because we are not running to them out of a sense of loss; we are not looking to our careers to give us meaning or transcendence or hope. We have found this in our communion with the eternal, triune God who has loved us and made us His own. So, we go to our jobs with hearts already full, with a stable sense of self. And, of course, we go about life knowing that good news about hell isn’t that it is only imaginary—we know that it is painfully real. The good news is that Christ defeated hell through His death and resurrection. And now, through the ministry of His Spirit, we are grafted into His Church—the heavenly bulwark against whom the gates of hell cannot prevail.

- In Juliet Schor’s book The Overworked American: The Surprising Decline of Leisure, she quotes James Pilkington, the Bishop of Durham, in 1570 describing what the common working man’s day consisted of:

“The labouring man will take his rest long in the morning; a good piece of the day is spent afore he come at his work; then he must have his breakfast, though he have not earned it at his accustomed hour, or else there is grudging and murmuring; when the clock smiteth, he will cast down his burden in the midway, and whatsoever he is in hand with, he will leave it as it is, though many times it is marred afore he come again; he may not lose his meat, what danger soever the work is in. At noon he must have his sleeping time, then his bever in the afternoon, which spendeth a great part of the day; and when his hour cometh at night, at the first stroke of the clock he casteth down his tools, leaveth his work, in what need or case soever the work standeth.”

To translate all that old timey English for you: work was pretty chill. Slow mornings, naps, lunch breaks, and a freedom to stop when quitting time came. Though your work would be from dusk to dawn (and probably involve manual labor), it wasn’t a “grind.” In fact, Schor calculates that when you take all of the holidays and feasts where work ceased in Bishop Pilkington’s day, 30% of the year was spent in leisure.

In Spain, it was 40%.

France: 50%. ↩︎ - Ibid. ↩︎

- And yet, somehow, the show also is hilarious. ↩︎

- One of Ricken’s line proves to be significant: “In the center of industry is dust.” In the final episode of season one, a representative for Lumon advertises the severance procedure as: “A kind and empathetic revolution that puts human beings at the center of industry.” Where is Lumon intent on taking human beings? To the dust.

After the fall into sin, the ground is cursed and Adam’s labor, his work, is now marred by toil and thorns: “By the sweat of your face you shall eat bread, till you return to the ground, for out of it you were taken; for you are dust, and to dust you shall return,” (Gen 3:19). In a fallen world, you work, and then die. ↩︎