Augustine’s Confessions detail approximately a 15-year-long struggle with God. His journey wanders through Manicheism, skepticism, and neoplatonism, before seriously considering the Christianity his mother taught him at a young age. After meeting regularly with the bishop, Ambrose, and attending church, Augustine’s intellectual arguments against Christianity (and the Bible) fade. He becomes compelled by the beauty and truth of Christianity and begins to see how inadequate his previous Manichean faith was.

But, becoming aware of the truth of Christianity was not enough.

I no longer had my usual excuse to explain why I did not yet despise the world and serve You, namely, that my perception of truth was uncertain. By now I was indeed quite sure about it. Yet I was still bound down to the earth. (Book VIII.v)

The Limits of Mental Assent

While Augustine confesses that Christianity is true, objectively speaking, he also realizes that he is anything but objective.

Over the course of Augustine’s life, he became deeply bound to two vices: worldly ambition and lust.2 But it is the latter that becomes the dominant weight. His sexual sin blocked the path to Christ:

They tugged at the garment of my flesh and whispered: ‘Are you getting rid of us?’ And ‘from this moment we shall never be with you again, not for ever and ever.’ (Book VIII.xi)

Augustine sees the choice before him—Christ or his lusts—and admits that while Christianity was “pleasant to think about and had my notional assent,” (emphasis added), the lusts of the flesh were simply “more pleasant and overcame me.”

Augustine compares himself with a man in a deep sleep who upon being shaken awake—and truly desiring to wake up—nevertheless sinks back into bed:

Though at every point you showed that what you were saying was true, yet I, convinced by that truth, had no answer to give you except merely slow and sleepy words: ‘At once’—‘But presently’—‘Just a little longer, please.’ But ‘At once, at once,’ never came to a point of decision, and ‘Just a little longer, please’ went on and on for a long while. (Book VIII.v)

Notice: Augustine wants to come to Christ and sincerely believes it is true. Yet, he only wants and believes to a certain point. Not enough to shake off the “sweet drowsiness” of the world.

I sighed after such freedom, but was bound not by an iron imposed by anyone else but by the iron of my own choice. The enemy had a grip on my will and so made a chain for me to hold me a prisoner. (Book VIII.v)

Augustine’s reservations were not intellectual; they were moral. He was in deep sexual bondage. He had a personal concubine for most of his adult life and could not bear to be without one. He knew that coming to Christ meant that this would have to change and he both wanted and didn’t want that to happen.

He would pray: “Grant me chastity and continence…but not yet.”

The Limits of the Will and the Power of Habit

What accusations against myself did I not bring? With what verbal rods did I not scourge my soul so that it would follow me in my attempt to go after you! But my soul hung back. It refused, and had no excuse to offer. The arguments were exhausted, and all had been refuted. The only thing left to it was a mute trembling, and as if it were facing death it was terrified of being restrained from the treadmill of habit by which it suffered ‘sickness unto death’ (John 11:4). (Book VIII.vii)

We are not, decisively, controlled by what our mind’s ascent to, but by what our hearts delight in. And this is where Augustine’s use of the role of habits in his conversion proves to be so illuminating for us today.

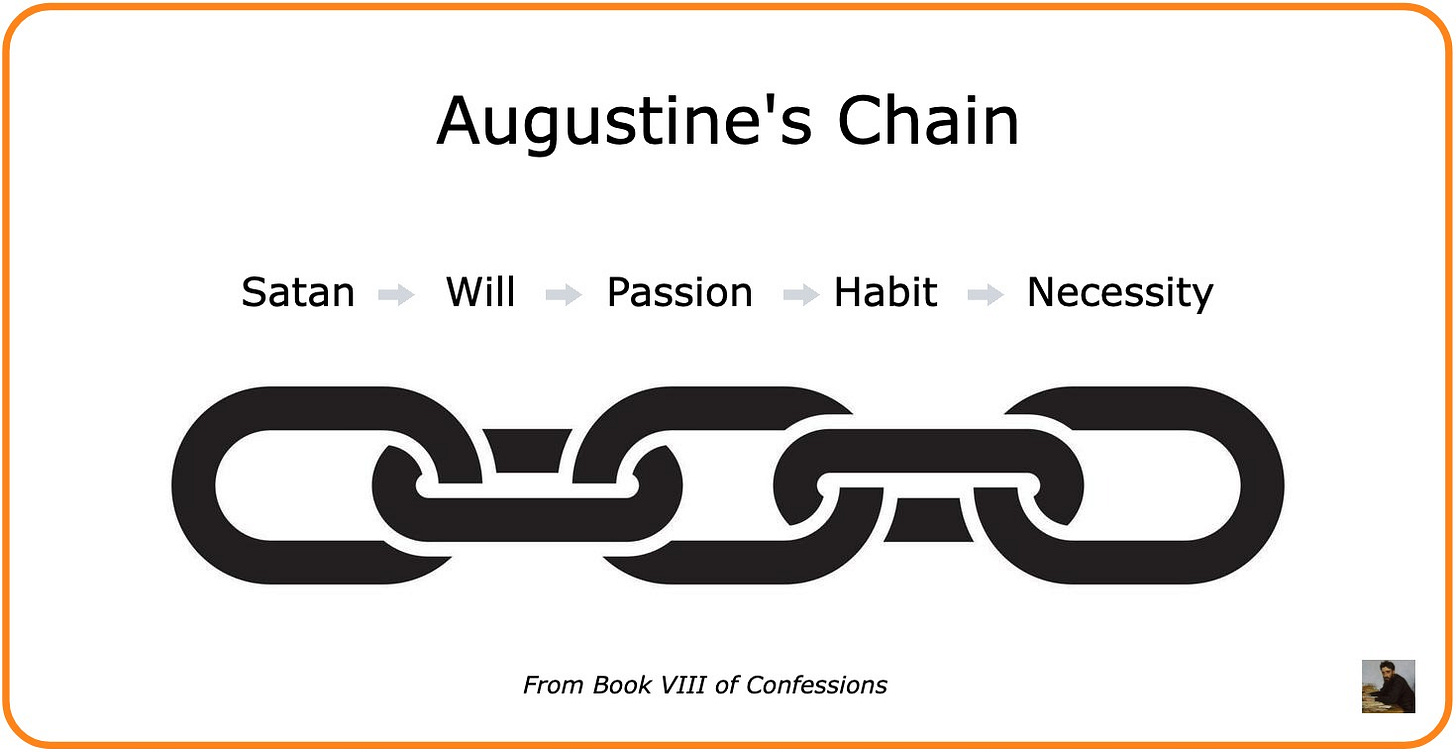

After lamenting that the enemy “had a grip on [his] will,” Augustine explains:

The consequence of a distorted will is passion. By servitude to passion, habit is formed, and habit to which there is no resistance becomes necessity. By these links, as it were, connected one to another (hence my term a chain), a harsh bondage held me under restraint. (Book VIII.v)

Augustine accepts responsibility for his sin while still affirming that he is under the “grip” of the enemy, and so is left with a will that is fundamentally bent.5 This distorted will creates inflamed passions—strong urges—that (when indulged) create the well-worn footpaths of habit. And once a habit is secured, it seems impossible to break (necessity).

Augustine was unfamiliar with modern brain science, but he is accurately describing the mechanism of habit-formation and the brain’s tendency to wire neural pathways together.

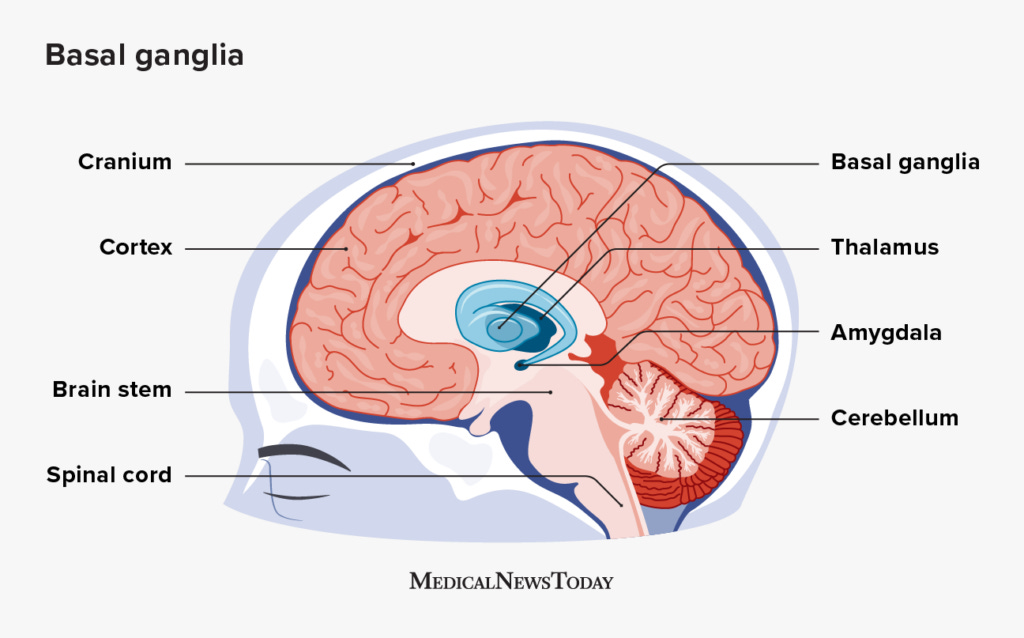

Our brains are designed for efficiency and are hungry for pleasure; if every time you wake up you brush your teeth or check your phone (pleasurable experiences), in time the various neurons that are firing in your brain to perform those activities will begin to fuse together, so that one (waking up) leads to the other (brush teeth, check phone). Eventually, you perform the task automatically. These habits are tucked away in the deep recesses of your brain responsible for emotions and memories (the basal ganglia) far away from the area responsible for conscious thought (the prefrontal cortex).6

Which means that much of what animates our decisions and actions happens beneath the surface of our awareness. They are murmurs that stir and ripple the deep currents of our mind, pushing us towards decisions long before we are aware. This is also why habits seem to be so impervious to change by mere thought alone, as if one could change the course of a river by paddling in the opposite direction.

Augustine has spent years practicing the habit of sexual indulgence. He has literally shaped his brain to be habituated towards this act. He has a growing set of new beliefs about Christianity and a desire to submit to God, but notice how frequently he speaks about the role of habit in preventing him from changing course:

The new will, which was beginning to be within me a will to serve you freely and to enjoy you, God…was not yet strong enough to conquer my older will, which had the strength of old habit.

I was responsible for the fact that habit had become so embattled against me; for it was with my consent that I came to the place in which I did not wish to be.

The law of sin is the violence of habit by which even the unwilling mind is dragged down and held, as it deserves to be, since by its own choice it slipped into the habit.

Meanwhile the overwhelming force of habit was saying to me: ‘Do you think you can live without [lust]?’

We are dealing with a morbid condition of the mind which, when it is lifted up by the truth, does not unreservedly rise to it but is weighed down by habit.

At the height of Augustine’s spiritual turmoil, he wanders into a garden “deeply disturbed in spirit, angry with indignation and distress.” Augustine hates himself deeply for his failure of the will, for his slavery to his habit of sexual indulgence, but self-hatred isn’t enough to grant him faith. One thing is necessary: “The one necessary condition,” for entering into peace with God, “was to have the will to go.” And this is what Augustine lacks.

Like a buoy slowly sinking under the weight of growing barnacles, Augustine’s mind is “weighed down by habit” (Book VIII.ix), and so not free to respond to the truth of Christ, not capable of possessing an unencumbered will.

Inwardly I said: Let it be now, let it be now. And by this phrase I was already moving towards a decision; I had almost taken it, and then did not do so…Ingrained evil had more hold over me than unaccustomed good. (Book VIII.xi)

Neuroplasticity and the Gift of a New Will

How can one be free from the enslaving habits that prevent us from following Christ? If Augustine’s diagnosis is correct, and our wills are bound by sin, and our brains are shaped by habits that strengthen this distorted will, then how can anyone be freed from it?

On the one hand, if Augustine can understand his habits to play such a crucial role in hindering his faith, we could consider basic ways in which habits are changed. If your mind’s map has a well-worn groove of habit formed, then you need something from outside your mind to help change it; mere thought alone will likely not do the trick.

For instance, if you want to stop looking at your phone as soon as you wake up, just telling yourself: “Don’t look at your phone,” likely will not be enough if the habit is well ingrained. You may need to move your phone off your bedside table, maybe out of your bedroom. The point is that you need more—not less—but more than thoughts alone to change your behavior. You need something external to rearrange your environment so that indulging the habit becomes harder. You reach for your phone right as you wake up and—it isn’t there.

Your brain creates synaptic pathways through repeated actions (helping form habits), but this same mechanism can be used to change habits as well. This capacity for the brain to structurally alter itself is known as neuroplasticity. If you stop performing an activity, in time, your brain begins to practice “synaptic pruning,” weakening the neural pathway and de-coupling it from other actions. In time, the well-worn path of habit fades.

The problem for Augustine, and for any of us who are examining the role of habits in the spiritual realm, is that changing the deep habits of unbelief are not so simple.

But the mechanism isn’t different.

What does Augustine need? What do we need? We need help from something, or Someone, outside of our minds. Mere willpower alone will not be enough. Augustine has already found this external help in a number of ways:

- He has begun attending church, interacting with fellow Christians, and enjoyed the benefits the Christian community. His deeply devout mother, Monica, has stayed in regular contact with him and (Augustine knows) she prays fervently for him every day. The decisive events that precede Augustine’s conversion is speaking with the bishop Simplicianus and his Christian friend, Nebridius, who share stories of how other Christians followed Christ. The community you keep has a profound impact on the habits of faith, for good or for ill.

- He has begun studying the Bible, listening to sermons, and speaking with the bishop Ambrose to discuss his questions. The very externality of the Word of God is a means by which something outside addresses the inner man. These are objective, external bumpers that Augustine’s inner man encounters and must conform to in order to understand. And it is this external word that proves decisive in his conversion.

When Augustine falls down in prayer under the fig tree, he hears a child’s voice call out: “Take up and read, take up and read!” Believing it to be a sign from God, he goes over and opens up the Bible to the book of Romans and reads Romans 13:13-14. Augustine explains:

I neither wished nor needed to read further. At once, with the last words of this sentence, it was as if a light of relief from all anxiety flooded into my heart. All the shadows of doubt were dispelled. (Book VIII.xii)

But what was it that empowered Augustine in that moment to hear that external word and believe? He had heard the Bible read many times, studied it himself before. Why is it so piercing this time?

Earlier, Augustine sees a vision of Chastity in the form of a beautiful and dignified woman whose hands are filled with examples of other Christians who have forsaken the lusts of the flesh to abide in Christ. She asks Augustine:

‘Are you incapable of doing what these men and women have done? Do you think them capable of achieving this by their own resources and not by the Lord their God? Their Lord God gave me to them. Why are you relying on yourself, only to find yourself unreliable? Cast yourself upon him, do not be afraid. He will not withdraw himself so that you fall. Make the leap without anxiety; he will catch you and heal you.’ (Book VIII.xi)

Like a man on a sinking ship terrified to jump in the water, Augustine has been paralyzed, incapable of making the leap of faith. And this halting paralysis (I must jump; I cannot jump; but I must…yet I can’t) is what makes Augustine’s conversion so painful. He knows he cannot remain where he has been, but doesn’t see how he can muster the willpower to leap into Christ. Lady Chastity exhorts him: focus less on your power to leap; focus instead on Christ who can catch even the most fainthearted of stumblers.

And then, at the moment upon reading Romans under the tree, Augustine suddenly believes. What happened?

Augustine puts it simply: “You converted me to yourself.”

God gave Augustine a new will.

The nub of the problem was to reject my own will and to desire yours. But where through so many years was my freedom of will? From what deep and hidden recess was it called out in a moment?…Suddenly it became sweet to me to be without the sweets of folly. What I once feared to lose was now a delight to dismiss. You turned them out and entered to take their place. (Book IX.i)

The wonder of Christianity is that it is not merely an external framework that bumpers and corrals our base desires; to change bad habits for good ones through the power of our own will.

The wonder of Christianity is that God—the Ultimate External Reality—can thrust Himself into the depths of our enslaved mind, heart, and soul and snap the chains of the flesh. The Wholly Other outside of us can enter in, walk into the most interior of interiors…and transform us, from the inside out; can help reorient the very structure of our brains and overcome our own weakness.

Practical Takeaways

- Augustine’s conversion was a process. There was the decisive moment of tolle lege, but that was the culmination of years of exploration and meditation. We should be slow to judge the end of someone’s story by where they are at today. And though God ordains specific moments in time where the lost soul crosses the line of salvation, that punctiliar moment may be quite difficult for us to discern as people generally move across a gradual spectrum from unbelief to belief.

- We shouldn’t discount the supernatural consequences of natural habits in our lives. If a man has a habit of walking past the doorway of a prostitute, we shouldn’t be surprised that this will eventually affect his soul (Prov 5:8). Our lives are a collection of a million, billion little decisions—most of which seem fairly inconsequential. But when we scoop them all together, we find a particular shape and pattern. And those decisions (and habits) bear influence on our spiritual lives. If you find yourself locked into a position of unbelief, examine the habits of your life and how they may be contributing to resisting Christ. Fill your life with external aids to nudge you closer and closer to faith: go to church, read the Bible, listen to Christian music, devote time to pray (even try praying on your knees), speak with other Christians about the questions and doubts you have, go to bed on Saturday night early so you can be attentive in corporate worship, and avoid habits which actively dampen your spiritual exploration.

- If you are in that agonizing place between faith and skepticism, take heart that your situation is not unique. Many other Christians have experienced the same thing. Don’t fixate on your lack of faith, your split will, your halting reservations. Look to Christ. He can give you faith, He can give you the will you need, the strength to yield to Him. He can change the habits which weigh us down. There is such relief and joy in leaving the see-saw of indecision, of collapsing fully into Christ.

You called and cried out loud and shattered my deafness. You were radiant and resplendent, you put to flight my blindness. You were fragrant, and I drew in my breath and now pant after you. I tasted you, and I feel but hunger and thirst for you. You touched me, and I am set on fire to attain the peace which is yours.